Deconstructing Epidemiological Data for Courts

Significance Is Not Enough

Most of my career has involved conducting and evaluating research. As a member of a Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), my role was to ensure the safety of the participants and the scientific validity of the study. As the chair of the Institutional Review Boards (IRB), my responsibility was to protect the rights and welfare of human subjects. I had to ensure that the study was ethical, that risks were minimized, and that informed consent was obtained appropriately. But what is the role of an epidemiologist in legal matters? This article provides an overview of the role of research experts in litigation.

Background

In medical class action lawsuits, epidemiological evidence frequently serves as the foundation for establishing general causation. For example, plaintiffs may claim exposure to a drug caused substantial harm. The epidemiologist’s charge is to weigh the evidence and quantify the plausible risks associated with such exposure.

Much of the emphasis in clinical research is on statistical significance, which indicates only that an observed association is unlikely to be due to chance. Significance conveys nothing about the magnitude, severity, or practical relevance of the association. Consequently, it is not very convincing in court.

The role of the expert is to guide the court beyond the binary consideration of statistical significance and instead address the more critical questions regarding the magnitude and practical implications of the observed effect. This consideration leads to the concept of effect size.

The Distinction Between Statistical and Practical Significance

For example, consider a study of a widely used pain reliever involving one million subjects. The study may find a statistically significant increase in mild headaches among users compared to non-users. However, if the increase is from 10% in non-users to 10.01% in users, the result, while statistically significant, lacks practical importance.

Conversely, a small study may demonstrate a substantial increase in a rare, severe cancer among exposed workers. Still, due to the limited sample size, it may narrowly fail to meet the 0.05 threshold for statistical significance. Dismissing such findings solely based on the p-value could have significant public health and legal consequences. In litigation, interpreting effect size is essential for understanding the real-world impact of exposure on class members.

Key Epidemiological Measures of Effect Size

In medical epidemiology, when the outcome is dichotomous (e.g., disease occurrence versus non-occurrence), two primary effect-size measures are used: Relative Risk and Attributable Risk.

1. Relative Risk (RR) or Hazard Ratio (HR)

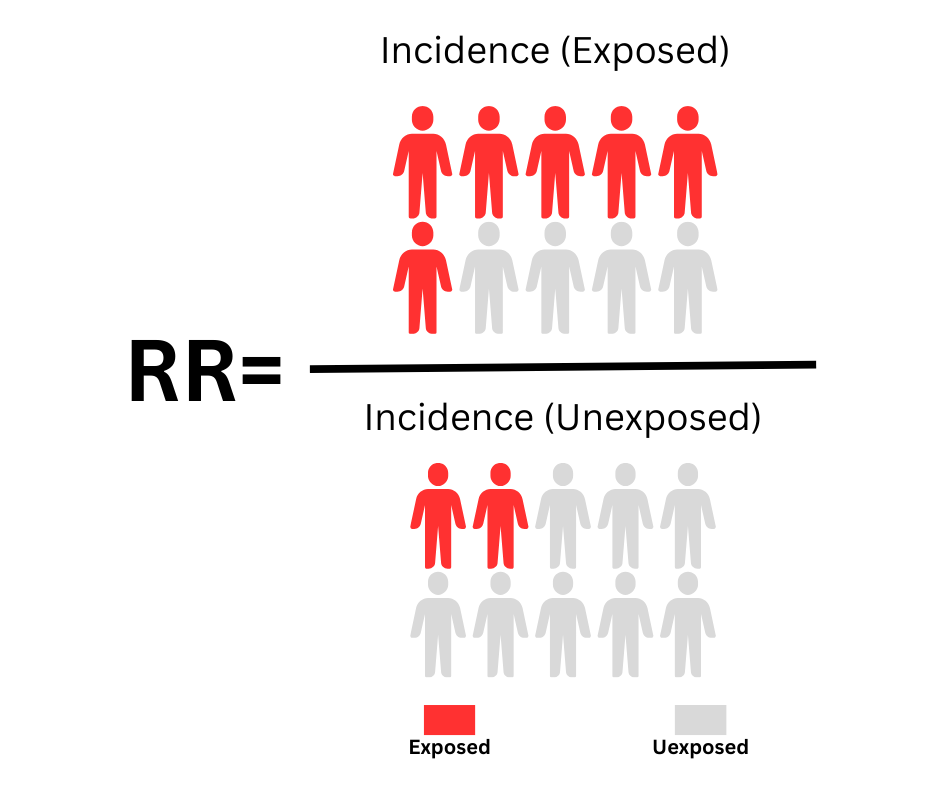

This is the most common measure of association strength. It indicates how many times more likely exposed individuals are to develop the disease than unexposed individuals and is expressed as a ratio. An RR of 1.0 indicates no association, meaning the risk is the same in both groups. An RR of 1.5 indicates a 50% increase in risk in the exposed group. The following figure shows the formula for estimating relative risk:

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

Interpreting Magnitude (Rules of Thumb)

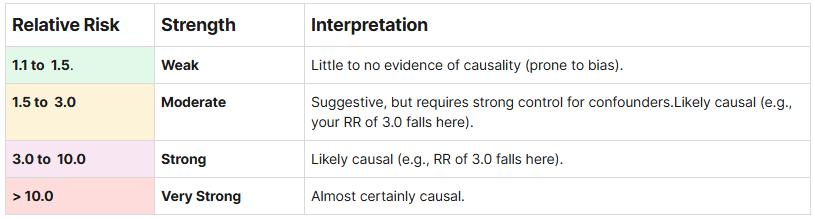

Unlike other standard effect-size measures, there are no rigid cutoffs for “small, medium, large” RR values because clinical significance depends on the severity of the outcome. However, in epidemiology (mainly observational studies where confounding is common), these thresholds are often used as heuristics.

The “Magic Number”: Relative Risk Greater Than 2.0

The legal threshold of RR> 2.0 is a critical concept for expert witnesses.

In tort claims, the plaintiff must establish Specific Causation, demonstrating that the exposure caused their specific injury, rather than merely showing that the exposure can cause the injury in general (General Causation).

The Logic: If the background rate of an outcome (e.g., disease) is 1 in 100, and the exposure increases that rate to 2 in 100 (RR = 2.0), then for every 2 cases in the exposed group, 1 is background, and the exposure causes 1.

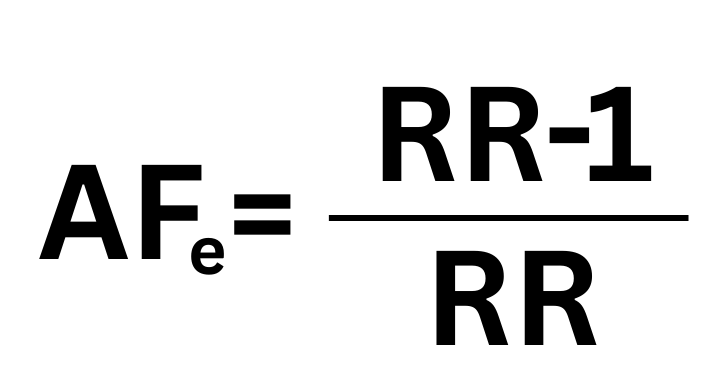

The Math: The “Attributable Fraction in the Exposed”

When RR equals 2.0, the Attributable Fraction in the Exposed (AFe) is 0.50 (50%). Any RR above 2.0 mathematically implies that the exposure is “more likely than not” (greater than 50%) to have caused the disease in a specific individual. If a meta-analysis demonstrates an RR of 1.5, the court may accept this as evidence of General Causation (the agent is capable of harm). Still, the defense can argue it is insufficient for Specific Causation because the probability that any given plaintiff’s illness was caused by the agent is only 33% (0.5/1.5), which does not meet the preponderance standard.

Interpreting Effect Size in the Courtroom

When presenting findings in a class action, the epidemiologist should provide context for the numerical results.

Strength and Causality: A large effect size, such as an RR of 3.0 or 4.0, makes a causal relationship more plausible than a weak association, such as an RR of 1.2, which may be attributable to unmeasured confounding factors. The strength of association is a key component of the Bradford Hill criteria for causation.

The “Preponderance of Evidence” Threshold: In civil litigation, the burden of proof is typically the preponderance of the evidence, defined as more likely than not (i.e., greater than 50%). Many courts consider a Relative Risk greater than 2.0 as a benchmark. An RR greater than 2.0 indicates that the background risk has more than doubled, suggesting that for any individual plaintiff in the class, it is more likely than not that their injury was caused by the exposure rather than by background factors.

The Scale of Harm: Attributable Risk helps quantify the extent of harm. For example, if the AR is 5 per 1,000 and the class size is 100,000, the epidemiologist can estimate that approximately 500 additional cases of the disease are attributable to the product in question.

Discussion

In the legal context, particularly in mass torts and class action lawsuits, epidemiological evidence is often the primary tool for establishing or refuting causation. Because it addresses population-level probabilities rather than individual certainties, this evidence is subject to intense scrutiny.

Courts serve as gatekeepers, ensuring that unreliable scientific evidence does not reach the jury. To achieve this, they subject epidemiological studies to rigorous reliability and relevance tests. Before a jury hears the evidence, the judge must determine whether it is scientifically valid. This refers to the Admissibility Standards (Dubert, 1993; Frye, 1923).

The Daubert Standard (Federal and many states): The judge assesses the methodology rather than the conclusion alone. Key considerations include whether the theory has been tested, whether it has been peer-reviewed, the known error rate, and its general acceptance within the scientific community.

The Frye Standard (some states): This older standard focuses primarily on whether experts in the field generally accept the method.

AI Tools for Evaluating Medical Evidence

References

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

Frye v. United States, 293 F. 1013 (D.C. Cir. 1923).