Digital Footprint Tracking Primer

Getting Started

Background

Nearly all individuals have a digital footprint, the trail of data generated by their online activity. This footprint encompasses both information intentionally shared, such as posts, comments, and photos, as well as data collected without the user’s explicit awareness or consent, including IP addresses logged during website visits and metadata embedded in images.

Types of Digital Footprints

Active digital footprints consist of, but are not limited to, the following activities:

Social Media: Posting photos, status updates, or comments on platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, or X (formerly Twitter).

Communication: Sending emails or text messages.

Accounts: Filling out online forms to sign up for newsletters, banking services, or shopping accounts.

Publishing: Writing blog posts or uploading videos to YouTube.

Passive digital footprints include, but are not limited to, the following forms of data collection:

Web Tracking: Websites utilize cookies to monitor visit frequency, record IP addresses, and determine user locations.

Device Data: Apps gather data on your device type, operating system, and battery level.

Search History: Search engines record user queries to build profiles for targeted advertising.

Geotagging: Photos automatically record the exact GPS location where they were taken.

Tracking an individual’s digital footprint is not inherently malicious. Journalists, law enforcement personnel, cybersecurity professionals, and investigators employ open-source intelligence (OSINT) to verify facts, identify vulnerabilities, and safeguard individuals. OSINT entails collecting and analyzing publicly available information to generate actionable insights. This approach can reveal exposed assets and potential threats before malicious actors exploit them.

How To Track Digital Footprints

Define the target and scope: Clearly specify the objectives of the investigation, such as verifying a job candidate, investigating cyber harassment, or assessing executive exposure. Establish boundaries to prevent unauthorized access to unrelated or protected data.

Collect publicly available information: Identify and examine social media profiles, domain and IP records, public databases, professional networks, forums, messaging applications, and news archives.

Analyze and correlate: Compare usernames, photos, and writing styles across multiple platforms to identify linked identities.

Geofencing and geolocation: Establish virtual boundaries around physical locations to collect data from application notifications or advertising networks, map Wi-Fi hotspots, and correlate findings with social media check-ins.

AI-driven pattern detection: Employ machine learning algorithms to detect sentiment, facial matches, or behavioral anomalies. Artificial intelligence automates the analysis of large datasets, transforming raw OSINT into actionable intelligence.

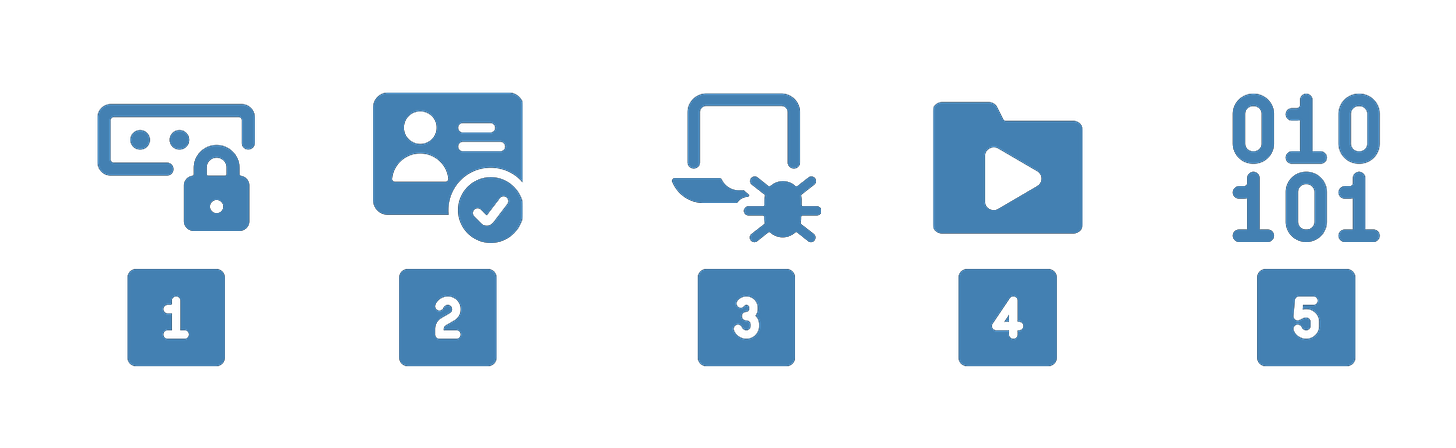

Step By Step

Collect initial identifiers: Begin with any known usernames, email addresses, phone numbers, or facial images.

Enumerate accounts: Utilize the collected identifiers to locate associated accounts.

Check for breaches: Assess whether any identifiers have been compromised or involved in data breaches.

Analyze related media: Examine images, videos, documents, or text posted by or associated with the subject.

Document the process: Provide a comprehensive description, such as a timeline, of the digital footprint investigation.

Digital Footprint Tracking Tools

Numerous commercial and open-source digital footprinting tools are available. Detailing each tool is beyond the scope of this article. In alignment with the principle of evidence deconstruction, this section focuses on challenges related to data accuracy. The following issues limit digital footprinting tools:

Inaccurate Profiling: Algorithms may misinterpret data. For instance, researching a stigmatized medical condition (i.e., depression) on behalf of a family member could result in the user being profiled as having that condition. Such misinterpretations may lead to irrelevant advertisements or, more concerningly, incorrect assumptions by organizations.

Fragmented Data: Information is frequently distributed across numerous platforms and data brokers. Reconstructing a comprehensive, accurate profile of an individual from these fragmented sources is challenging and error-prone.

Missing Context: Tracking tools can record user actions, such as website visits, but cannot infer underlying motivations. Without contextual information, these actions are easily misinterpreted.